When I first started doing layout for RPGs, I was given marked up text and I tended to use that early on. The copy would come from the editor or author and be full of what looked like HTML in brackets or angle-brackets: [em]this would be set in italics[/em], <dice>8</dice> would mean to put in an 8-sided die graphic, while [ih]this could be an inline header (and it took me forever to find out what “ih” meant). The work would consist of taking this plain, unstylized text, and doing several grep searches inside InDesign to replace the markup copy with stylized copy.

For projects like The Fate Codex, I had this pretty much down pat. It worked for that because that project was a series of documents, all using the same paragraph and character styles.

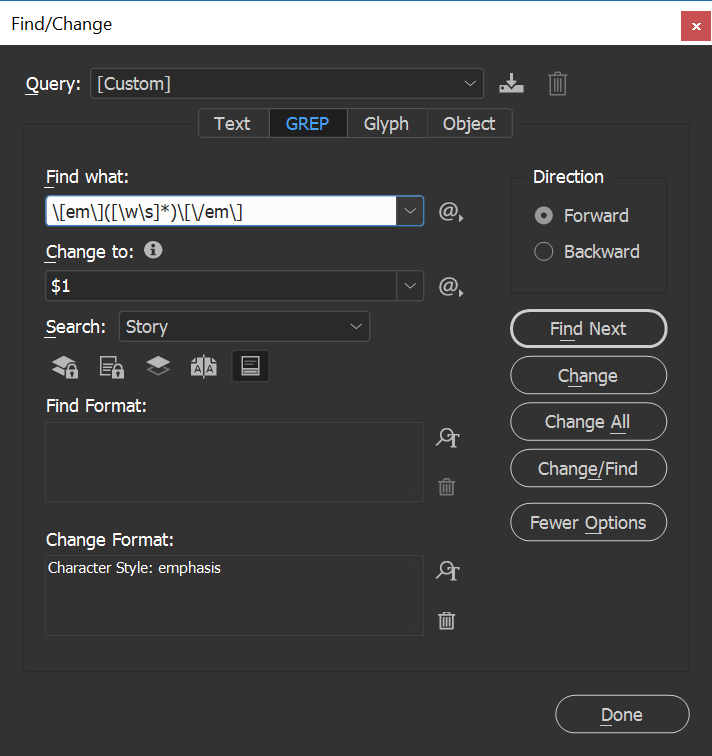

As an example, if I wanted to search for everything in an emphasis tag and stylize that copy to italic, I would use this grep search:

What that does is looks for anything with the pattern [em](at least one, maybe more, words and/or spaces)[/em], then replaces it with what’s in the parenthesis, and changes the format to the emphasis character style. That character style just has the Font Style set to Italic.

For The Fate Codex, I had more than a dozen of these grep queries saved: one for each of the three headers we used on the project, for bolding and italicizing, for bold italicizing, for bulleted lists, for embedded headers, for Fate stunts, for pregenerated character names and descriptions and stats and stress boxes and more.

And because that project was an anthology, we would get some writers who didn’t use our tags correctly: instead of an article header followed by a header 1, the writer may have tagged the article title as the header 1 and tagged what was supposed to be a header 1 as a header 2. So those saved grep queries would start stacking up: “h1 to h1”, “h1 to chapter”, “h2 to h1” — each with minor changes to catch those edge cases, mapping those tags to predefined styles.

…which is a long way to introduce how I prefer to handle character and paragraph styles inside InDesign.

In order to get all these grep queries to work, I needed to standardize my style names. ((Honestly, this is a thing I that I am still working on. Everything in the 7th Sea line has the same style names, but The Fate Codex might have different naming conventions.)) I want to have a character style called “emphasis”, all lower-case, to exist instead of “Emphasis”, because InDesign will see that as a different character style. In fact, if the character style is called “Emphasis” and I run the above query, all it will do is strip out the [em] and [/em] tags and not apply any character style to the text.

For my character styles, I start off with strong, which applies Bold; emphasis, which applies Italics; and strong emphasis, which applies Bold Italic. (I use these names because I used to program websites, and there was a move from the <b> and <i> tags to the <strong> and <em> tags. Habits.) Invariably, we’ll start adding in other character styles, like term, book title, and game title. Those few, I link back to to the strong, emphasis, and strong emphasis character styles.

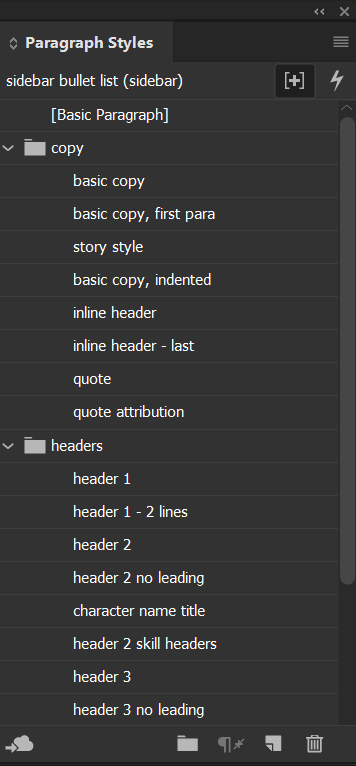

Over in paragraph styles, where we have [Basic Paragraph] as the default style InDesign starts with, I begin with two style groups: copy and headers and duplicate that [Basic Paragraph] style as basic copy. To the basic copy paragraph style, I define how the text in the book’s paragraphs are going to look. Every paragraph style is going to be based off of this one style.

As an aside, I have another habit with naming that’s particularly bad. I use the word “copy” quite a bit when referring to the words in the text. While this is the correct terminology for “the words in a manuscript”, the Adobe suite of products — Photoshop and Illustrator, mainly — uses the definition “a duplicate” when referring to “copy”. I find this occurring quite often in Photoshop when duplicating layers. If you duplicate a layer named black outline in that program and you get a new layer called black outline copy. That definition and that the windows (palettes) for layers in Photoshop looking identical to styles in InDesign sometimes throws me. ((The current version of InDesign places a number after the name if there is no number, so if I duplicate my basic copy style, InDesign suggests basic copy 2 as the name. If I duplicate a heading 1 style, it calls it heading 1 copy. Somewhat maddening.))

My tendencies with paragraph styles is to indent the first line and have no leading between paragraphs or no indentation but have leading between each one. ((Your editing software might call leading “paragraph spacing”.)) Regardless, when there is a header, I like to have the first paragraph following the header to not be indented and to not have leading between header and paragraph.

And there are headers. ((Or “headings”, which I still haven’t quite embraced. Habits.)) I start with top-level heading (the H1), then go to an H2 based off of the H1, and sometimes an H3 based off of the H2. There’s a chapter header that usually is different than these headings. In the list to the right, which is a simplified version of 7th Sea‘s paragraph styles, we have no chapter header defined within this group.

And there are headers. ((Or “headings”, which I still haven’t quite embraced. Habits.)) I start with top-level heading (the H1), then go to an H2 based off of the H1, and sometimes an H3 based off of the H2. There’s a chapter header that usually is different than these headings. In the list to the right, which is a simplified version of 7th Sea‘s paragraph styles, we have no chapter header defined within this group.

And a bullet point style gets us to six:

- basic copy

- basic copy, first para

- chapter header

- header 1

- header 2

- bullet list

And then… the outliers.

Let’s say you want a bullet list like the above list in your book. There’s actually two styles present: a bullet list that has the first five items, allowing one list item to fall after the next, and a bullet list, last style that includes spacing between that last list item and the following paragraph. We only need two bullet list styles because our paragraph style in this blog has a “space after” value set (and no indentation). If these paragraphs were indented and there was no spacing between paragraphs, our bullet list needs a third style to apply to that first list item. That new style will create space between the paragraph “And a bullet point style gets us to six:” and the line item “basic copy”. In other words:

- bullet list, first

- bullet list

- bullet list

- bullet list

- bullet list

- bullet list, last

Now we might have a second-level item in that list. New paragraph style.

Now we might have a second-level item in that list at the very bottom of the list. New paragraph style.

Now we might have a second paragraph in a list item. New paragraph style.

And if that might occur at the bottom of the list? And if there are third-level items? More paragraph styles.

- bullet list, first

- bullet list

bullet list, additional paragraph - bullet list

- bullet list

- bullet list, second level

- bullet list

- bullet list, second level, last

Those headings in that graphic above? There’s always leading (space above) used in our heading styles to visually separate them from regular body copy they might follow. Except… what if there’s a heading and it’s immediately followed by a subheading? So now we have heading 2, no leading. ((I consider this to be bad form. In my perfect world, there will always be some copy between headings.)) If the writers go crazy with headings, we could wind up with heading 3 and heading 4Â and — god forbid — a heading 5. And that means we’ll probably need “no leading” variants. ((And you can see that I need to standardize these in the above graphic. There’s basic copy, first para and basic copy, indented. But there’s inline header – last instead of inline header, last. Annoying. Bad Thomas.))

So. Why so many paragraph styles if we might only have, say, one heading 5 that has two lines of copy in the book? Can’t we just override those two lines of text?

Yes, you could. But if you link your styles — that is, have your heading 2 based on heading 1 in the General tab — and you need to change the typeface, alignment, case, color, or any of dozens of different attributes in your document, you can make that change and it will cascade down through your linked styles.

All my headings were set in Aller and I need to change them to Dax? I make the change in the heading 1 paragraph style and it cascades all the way down to that annoying two-line heading 5.

Unless we did an override on that heading. Then we’ve got to hunt through this 328-page monstrosity of a book, searching for any heading in the book that’s been overridden with leading and typeface.

There’s also the “What if I get hit by a bus?” question. Handing off a document to a client or other layout artist is much smoother if there are descriptive names for your paragraph styles and there aren’t any difficult-to-notice overrides.

So, what do 7th Sea‘s paragraph styles look like? ((Assuming I get rid of a few unused styles?)) There’s the copy style group, which holds basic copy;Â basic copy, first para; and basic copy, indented. This style group also contains two different quotation and attribution styles, four styles total. There’s an inline heading style here and an inline heading, last style. An example text style. Some one-off styles, like the traits for the Knights of Avalon, which only appear in two books. And then there’s the lists, which include all the things from a few paragraphs above, plus numbered lists and roman numbered lists. Variants on the headings (which go down to heading 4). A style folder for sidebars. One for actual tables and one for faux tables (the character Backgrounds). The table of contents styles. The credit block. The quick statbars for Villains and full statblocks for Heroes. The page numbers and book titles and chapter titles that appear at the bottom of the pages. That ship we have there? That’s in a typeface, so there’s a paragraph style for that.

There are 95 different paragraph styles used in the 7th Sea line.

Not all of these are used in each book. The Heroes & Villains book has character sheets/stat blocks for characters. The 13 statblock styles won’t all be used in other books, but some of those will as we have stats for Villains in our sourcebooks. Some styles are created for a new book in the line, like that header 1, 2 lines style, when we suddenly had writers submit really long headings for a section. ((Or my favorite, a variation of character name when we had a writer create a really long name and title for two villains in the book. These had to fit on one line, so there’s a character name style where the text is set at 24t, and a version set at 16pt so we could get the entire name on one line called character name, fucking long version.))

So maybe start with six, maybe wind up with a dozen. Maybe wind up with a hundred.

This writing was generously supported by my patrons. You can motivate me to create more writings about layout, game design, and layout in games by becoming a patron. Find out more about my writing goals (plus my secret goal) on this site’s Patreon page.